On our love for books

29 August 2014

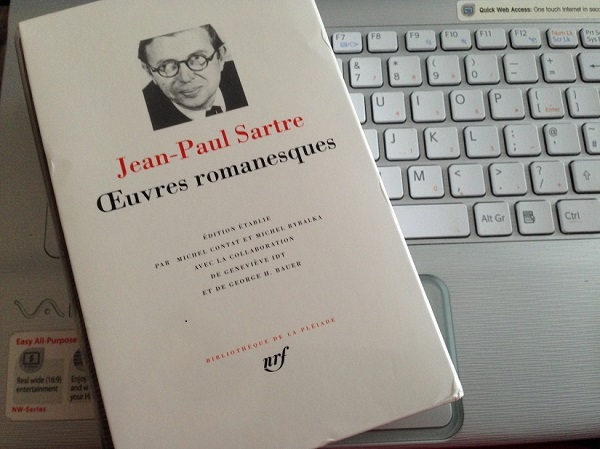

Sartre, Oeuvres Romanesques, Collection la Pléiade.

Books are like lovers. If you abandon them, they take revenge. And they always win.

It was a magnificent day in Paris, two days ago, and my return train to London was leaving in three hours. I was in a hurry to get back to the hotel, collect my stuff and head to the station. Just before turning onto Rue Vaugirard, a bookshop springs out from nowhere, right under my nose. I would have perhaps managed to ignore it, in the circumstances, had it not been for the tables outside. So clean and tidy at the front, more messy and grey at the back. The usual mix of literature – old and new, leather-bound and scruffy. The philosophy books were leading the show, right in the front row, and unbearably white. Collection: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Sartre, Camus, Platon. Coup de foudre, without a chance. I take in the view and try to focus my sight and my mind on as many individual books from that row as possible. As it turns out, my focus range is not something to boast about – so after a few moments of panic, I stop at Sartre. Oeuvres Romanesques published by Gallimard in 1982. It includes Nausea, the four volumes of Ways to Freedom, some extracts from his diary, and fragments of his correspondence with Simone de Beauvoir. (See below).

Voici le sommaire de ce volume: – Préface, chronologie, note sur la présente édition. – La Nausée. Le Mur. Les Chemins de la liberté: I. L’Âge de raison; II. Le Sursis; III. La Mort dans l’âme; IV. Drôle d’amitié. – Appendices: Dépaysement; La Mort dans l’âme (fragments de journal); La Dernière Chance (fragments). – Notices, notes et variantes. Bibliographie générale.

Equally irresistible is the unexpected – the ‘inedit’, as the French would say. The fact that the Nausea includes some bits of text initially removed by Sartre. The additional (largely unknown) pages from a war diary, published as Death in the Soul. And the correspondence with Simone de Beauvoir, about The Age of Reason. Indeed: La part de l’inédit dans ce volume est importante. Elle est constituée d’abord par l’intégralité des passages de La Nausée supprimés par Sartre. Puis par la nouvelle Dépaysement retirée in extremis du recueil Le Mur. Par le journal de guerre intitulé La Mort dans l’âme. Enfin par des fragments de ce qui devait être le tome IV des Chemins de la liberté. Inédits aussi certains documents publiés avec les notes, comme la correspondance entre Sartre et son éditeur à propos de La Nausée et une précieuse série de lettres à Simone de Beauvoir concernant la rédaction de L’Âge de raison.

I hold it and I realise that I don’t just like this book, I love it. Without even looking inside it. The price is high, and there is only one copy of it – and it is not a new one. That wouldn’t normally bother me, if only I had more time to explore it, to ‘get acquainted’, establish a rapport before becoming partners forever. But time I don’t have. So I decide to do ‘the sensible thing’ and walk on, resist buying it on an impulse. And through some miracle, I actually do. I put it down and I move on. I manage not to look back. Although with every step I take, I feel the distance increasing between myself and the book – as though it were the only one on earth, the last one I would ever hold in my hands. It was painful – and unnecessary, because I had the money and the time required to pay for it and walk away with the book in my hand. I just didn’t. For some odd, uncanny reason, I thought that it would be sensible not to buy the book in a hurry, to just focus on what I was supposed to do – walk back to the hotel, get my stuff, and head to the railway station. Strange mechanism this preconditioned kind of mental state. It’s almost as though our mind works against us, as full-bodied, full-souled people.

On the train, I tried hard to forget about the book I’d left behind, and focus on those I had with me – one brought with me from London, three new books and four philosophy magazines I’d bought the previous days in Paris – and all the electronic articles and notes from my iPad. I manage, but only somewhat. It is hard to ignore the conviction that, if the train hadn’t already left the station, I would have gone back to the bookshop and bought the book.

I also thought that, once back to work the following day, I’d be too busy to remember the book. And it’s true – the first day I was too busy to do anything about it; but not too busy to keep thinking about it.

The second day I did it: I bought it online (for more than it would have cost in Paris, of course). And now I have another two weeks of waiting. Maxim 17 days, to be precise. (It should arrive by the 15th of September). Ordered yesterday, dispatched this morning. I should perhaps write a journal d’attente. Watch this space.

My incantations must have helped, since the book arrived eleven days early – on 4th of September, while I was at work. They left it with our neighbours, who have two young children who must have been asleep by the time I arrived in the evening, so I had to wait another day in order to claim it. But after all the way, on a beautiful afternoon (the 5th September 2014), the book and I were finally reunited. Or introduced, I should say – since this was, of course, a different copy from the one I’d seen in Paris. Much more expensive too, according to the label on the box. I was so excited to finally hold it in my hand that I couldn’t yet focus on the content. I weighted it in my arms, and I took it all in – the beauty of the edition, delicate and sturdy at the same time. According to the last inside cover, I was holding volume number 295 of this precious Pléiade.

Good morning, Ana-Maria

I enjoyed this blog very much. The feelings evoked reminded me of the lyrics of a song called National Steel, written by Clive James:

Shining in the window a guitar that wasn’t wood

It was looking like a silver coin from when they still were good

The man who kept the music shop was pleased to let me play

Although the price was twenty times what I could ever pay

Pick it up and feel the weight and weigh the feel

That thing is an authentic National Steel

A lacy grille across the front and etchings on the back

But the welding sealed a box not even Bukka White could crack

I tuned it to an open chord, picked up the nickel slide

And bottlenecked a blues that sounded cold yet seemed to glide

The National Steel weaves a singing shroud

Just as sure as men in winter breathe a cloud

Scrapper Blackwell, Blind Boy Fuller and Blind Blake

Son House or any name you care to take

And from many a sad railroad, mine or mill

Lonnie Johnson’s bitter tears are in there still

Be certain, said the man, of who you are

There are dead men still alive in that guitar

Back there the next morning half demented by desire

For that storybook assemblage of heavy plate and wire

I sold half the things I valued but I’ll never count the cost

While I can pick a note like broken bracken in the frost

And I hear those fabled names becoming real

Every time I feel the weight or weigh the feel

Of the vanished years inside my National Steel